Red-black trees can be difficult to understand. In particular, the operations prescribed to handle the various cases one can encounter when performing insertions and deletions can seem pretty arbitrary and unmotivated. In this post, I hope to provide an intuitive derivation of these operations.

First, recall that a red-black tree must satisfy the following requirements:

We will refer to number 3 as the “red rule” and number 4 as the “black rule.”

The core operation underpinning almost any implementation of a self-balancing binary search tree is a rotation. A rotation can be thought of as the simplest transformation you can perform on a tree which preserves its binary search property.

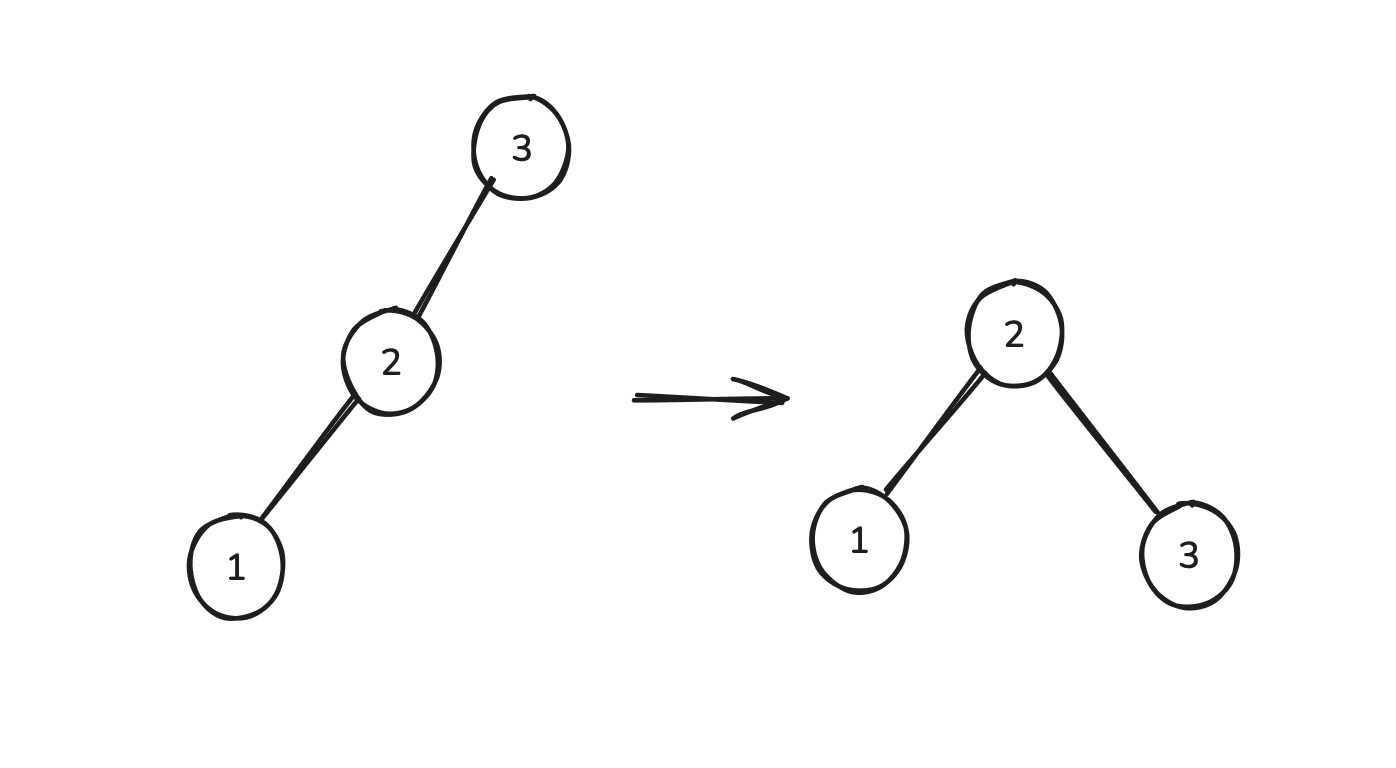

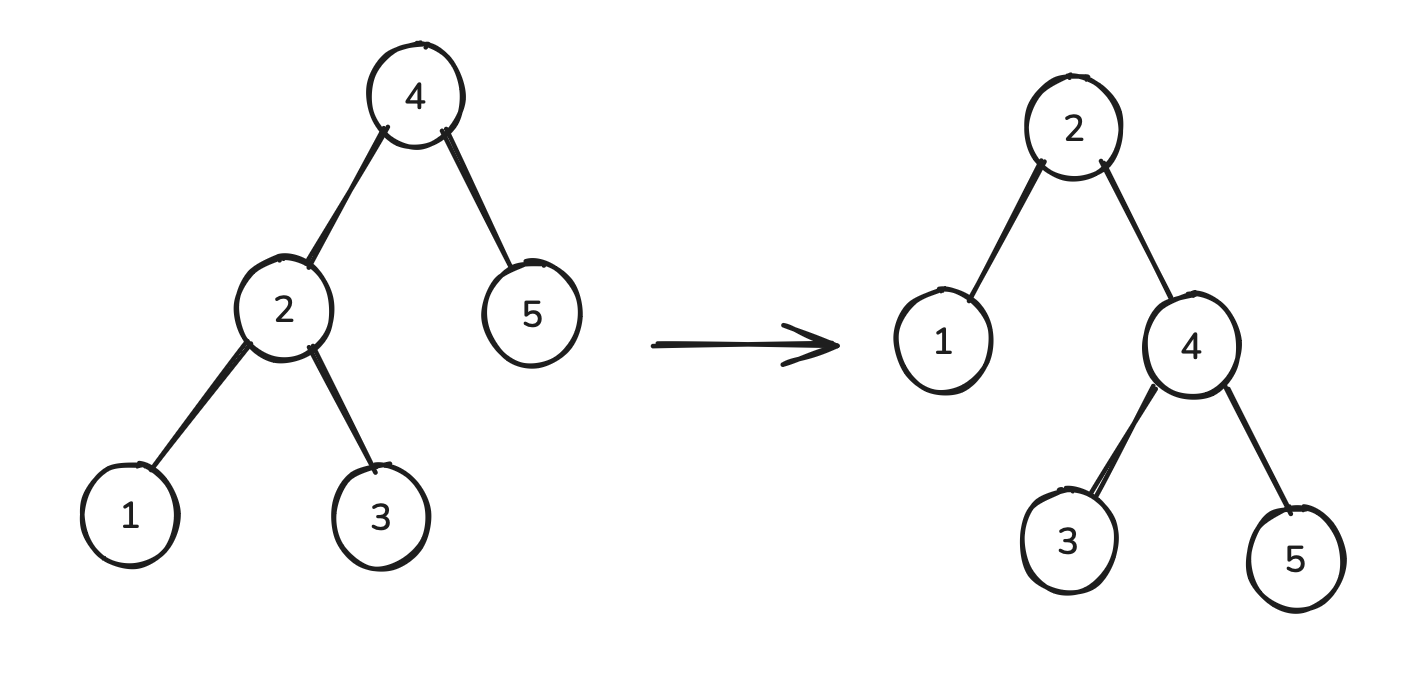

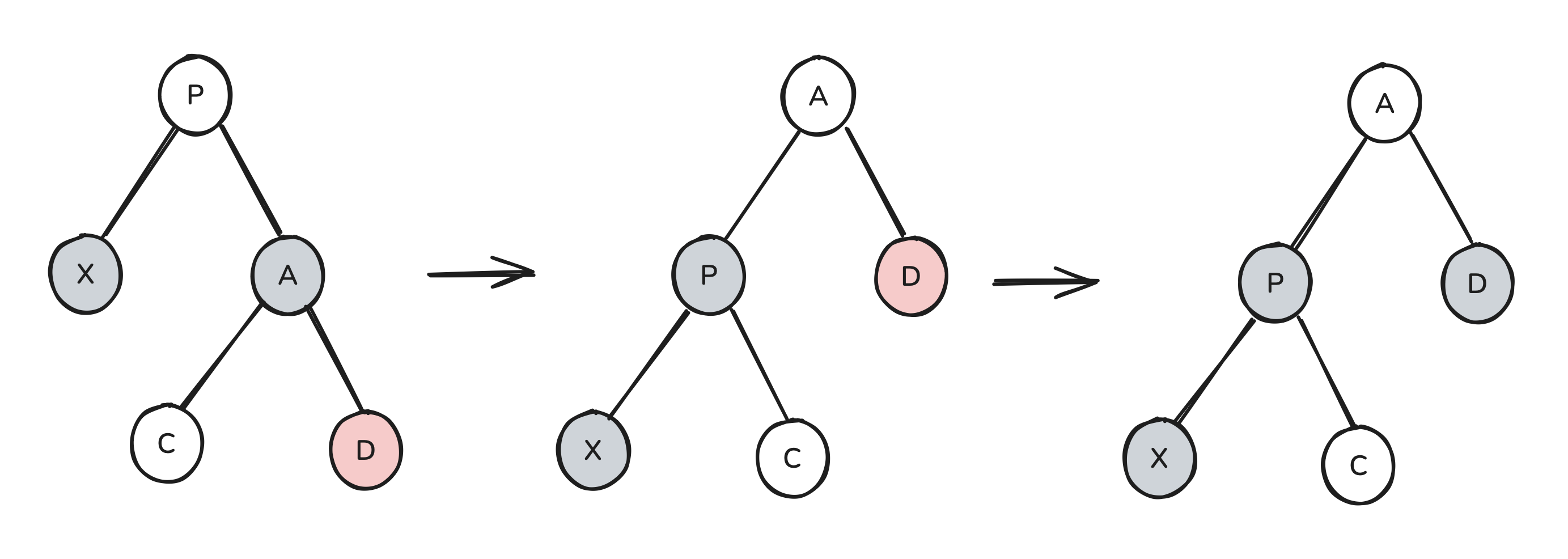

This is what a rotation does:

A rotation is essentially an expression of the fact that A being a left child of B and B being a right child of A are both valid ways to express that A < B.

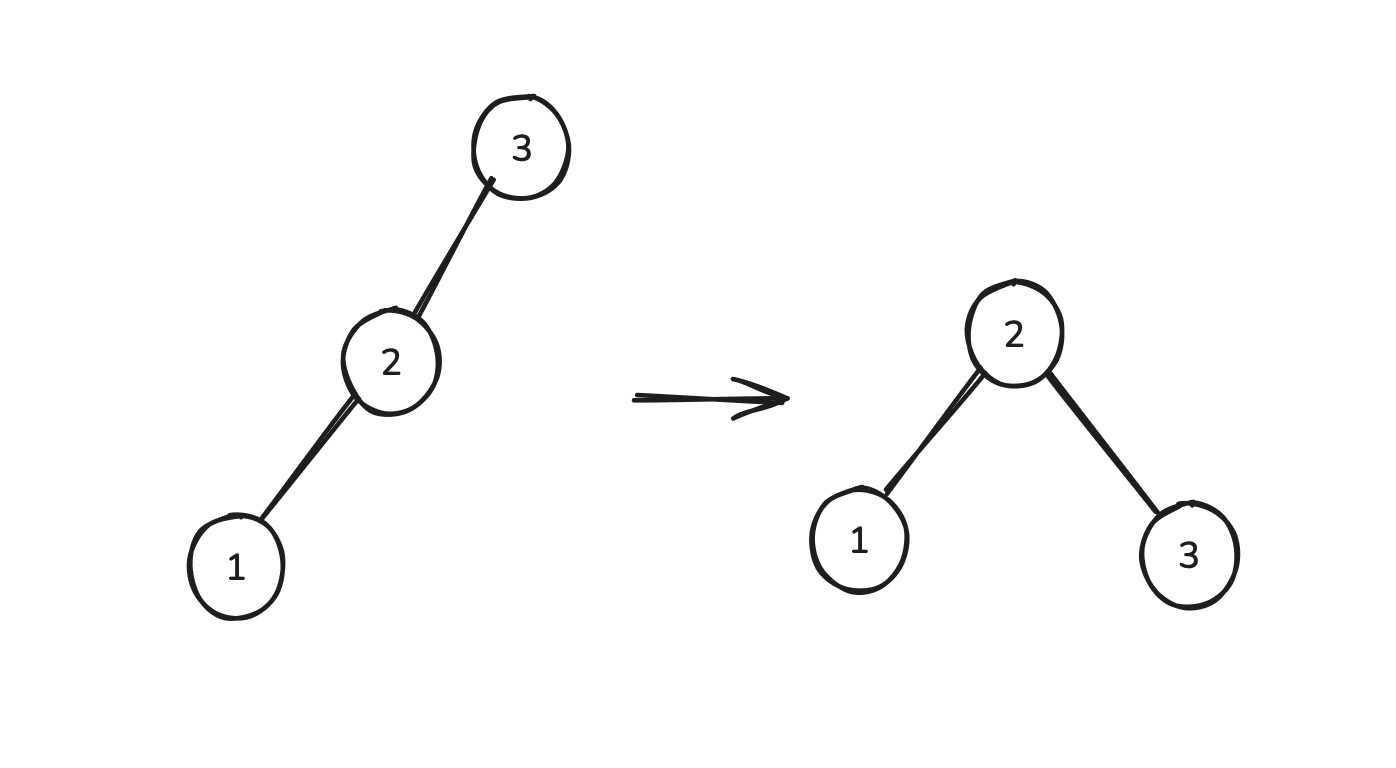

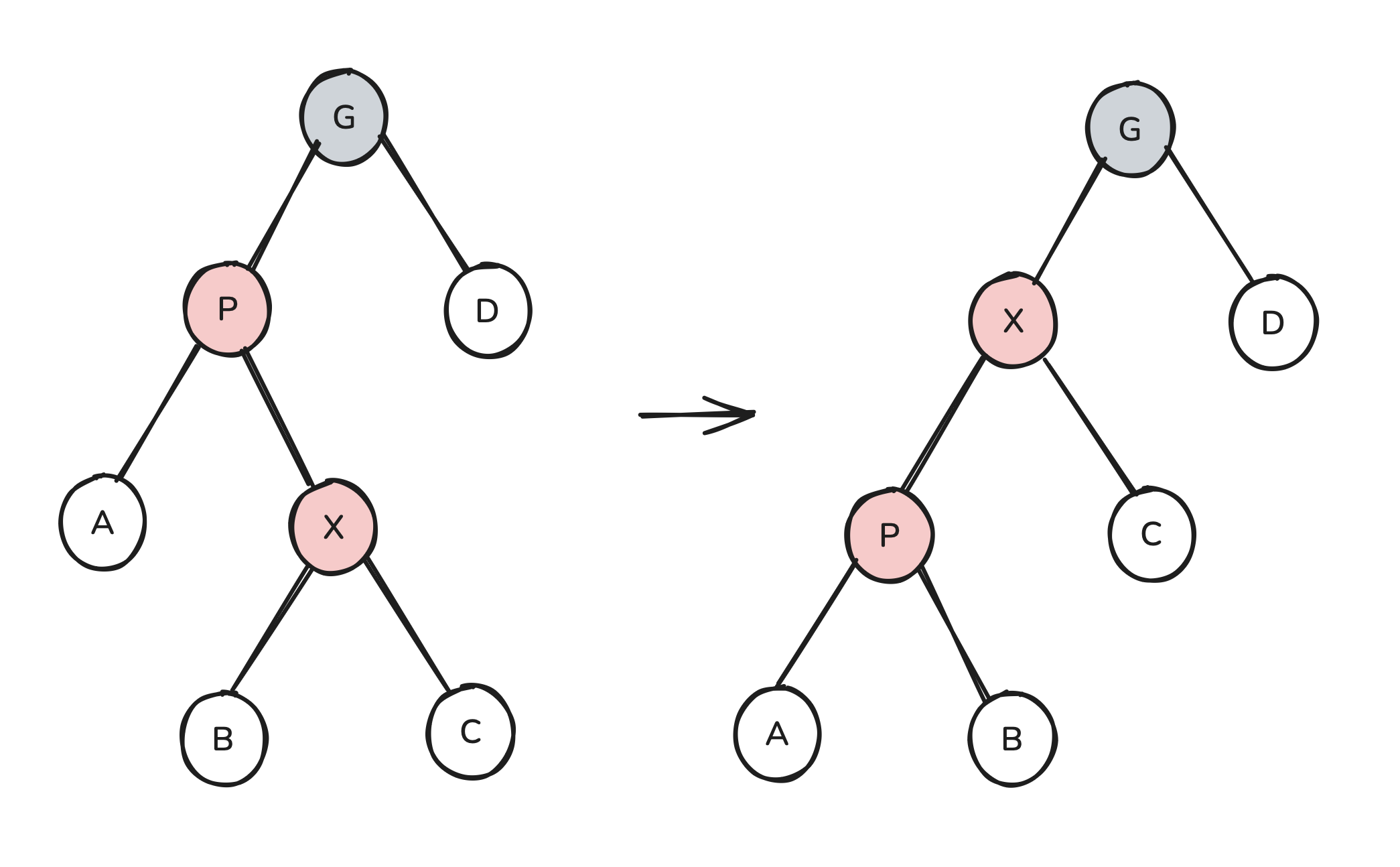

Note that in the above example, node 2 gains a child. This is okay because it starts off with one child. However, if it started off with two children, we must avoid it ending up with three children. So what we do is transfer its original second child to its grandparent when we perform the rotation:

In this example, we’ve switched node 3 from being a child of node 2 to being a child of node 4. Observe that we’ve preserved the binary search property because both before and after the rotation, node 3 was a right descendant of node 2 and a left descendant of node 4.

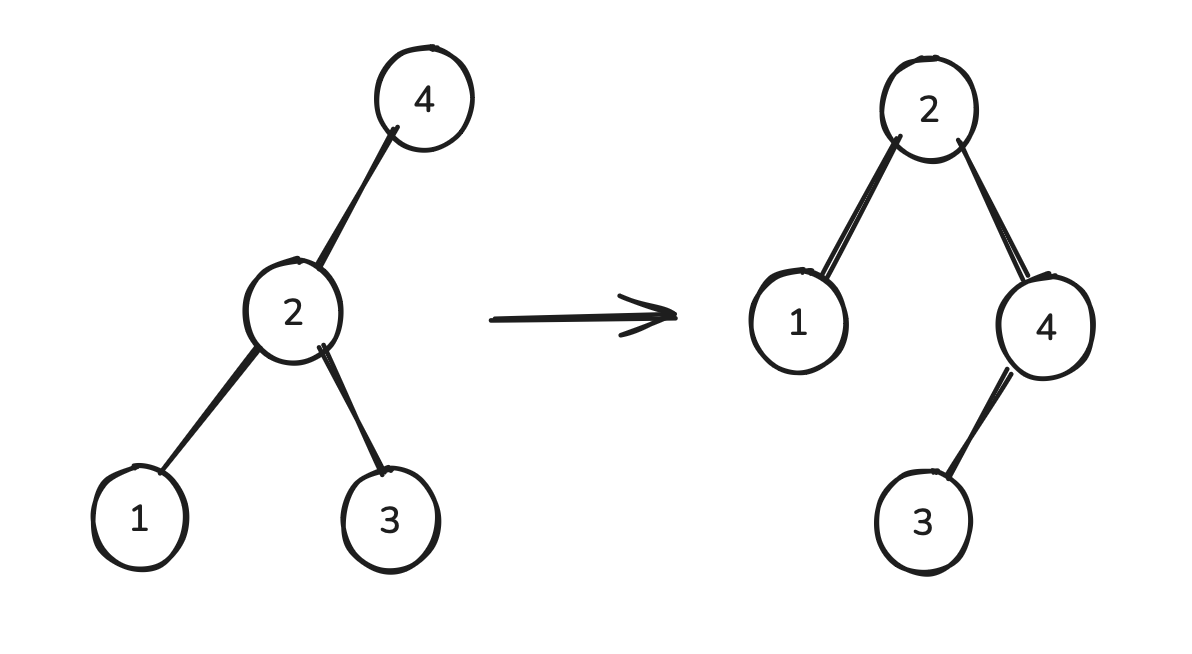

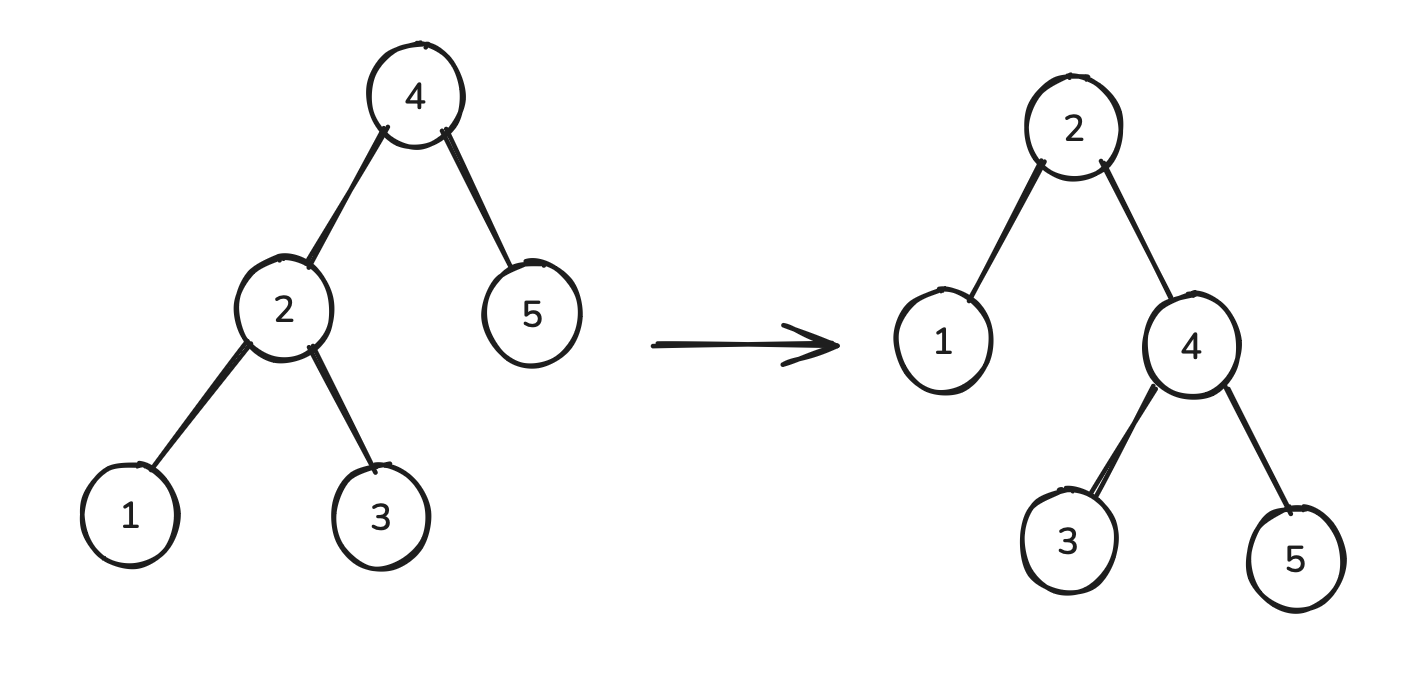

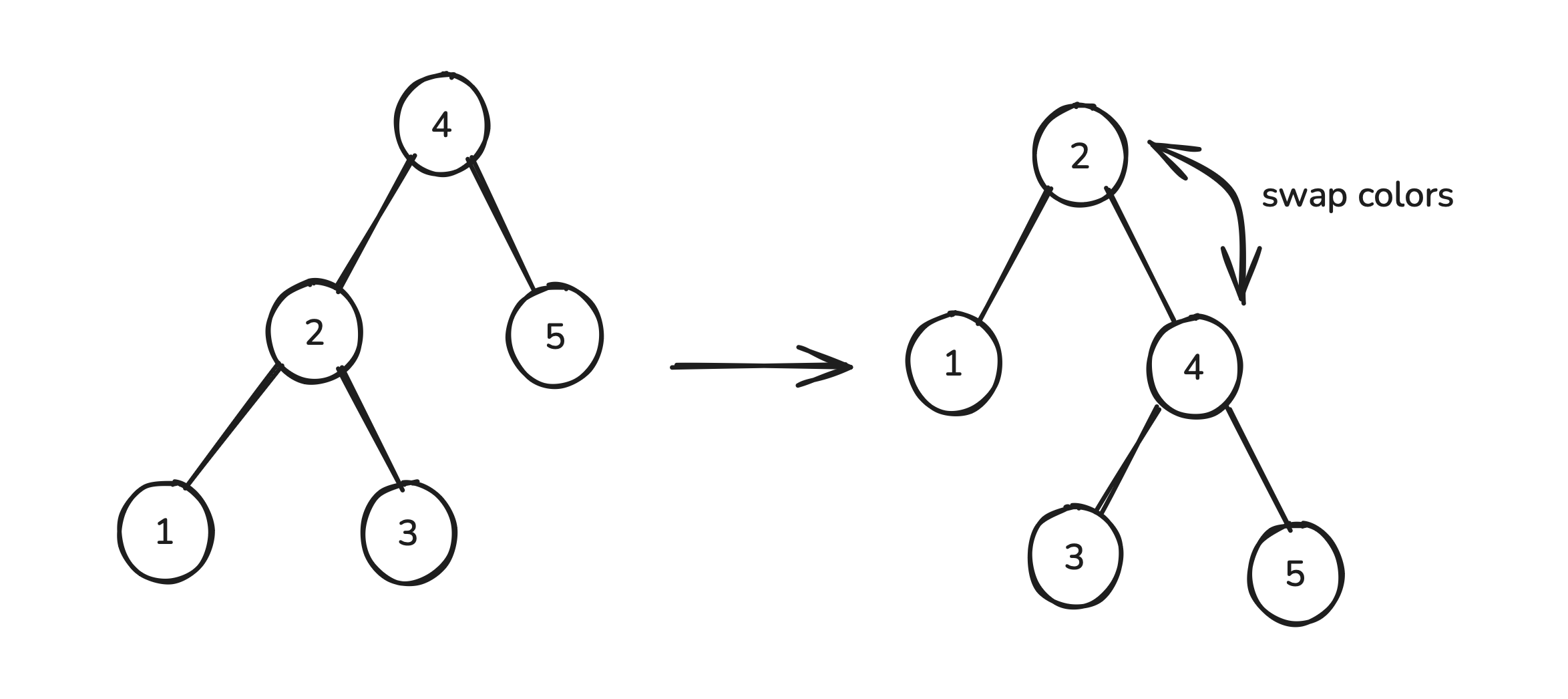

Finally, we’ll show the same rotation, but we’ll add an additional child to node 4.

We refer to the above operation as “rotating node 2 into node 4.”

We are able to perform rotations on subtrees. So in the above image, the nodes displayed could be part of a larger tree.

We will now explore how rotations interact with the black rule. Doing so will equip us with useful insights which will aid us in rebalancing our red-black tree in various scenarios.

If our original tree satisfied the black rule, then under what circumstances would the black rule be violated after a rotation is performed?

Note that any path to one of our tree’s null nodes must go through either node 1, node 3, or node 5, both before and after the rotation. Thus it suffices to examine how the ancestors of those three nodes have changed. We can gather the following:

Thus if either node 2 or node 4 were black in the original tree, then we’ve now violated the black rule. Otherwise, the black node counts of all paths have remained the same and we are fine.

It’s now possible to observe something interesting. Consider what happens if we swap the colors of nodes 2 and 4 after performing the rotation. Since both nodes 2 and 4 are ancestors of node 5, node 5’s set of ancestors isn’t altered by the swap. However, node 1’s post-rotation parent now has node 4’s color instead of node 2’s. Thus the overall effect of this operation now becomes:

Thus we can think of what we’ve done as having “transferred” node 2 from the ancestry of node 1 to the ancestry of node 5. Thus whether or not we’ve violated the black rule now only depends on node 2’s color. In particular:

We will refer to the operation of performing a rotation and then performing a color swap as described above as a rotate-swap operation. Moreover, when a red node is being rotated into and then color-swapped with another node (of any color), we will refer to the operation as a red rotate-swap, and when a black node is being rotated into and then color-swapped with another node (of any color), we will refer to the operation as a black rotate-swap. We can now make the following statements:

We’re now ready to investigate red-black tree operations. We will begin with insertion.

When we insert a node, we can choose to color it red or black. Coloring it black will definitely violate the black rule. Coloring it red will possibly violate the red rule. It seems easier to handle a red rule violation than it would be to handle a black-rule violation, so we will choose to color the node red.

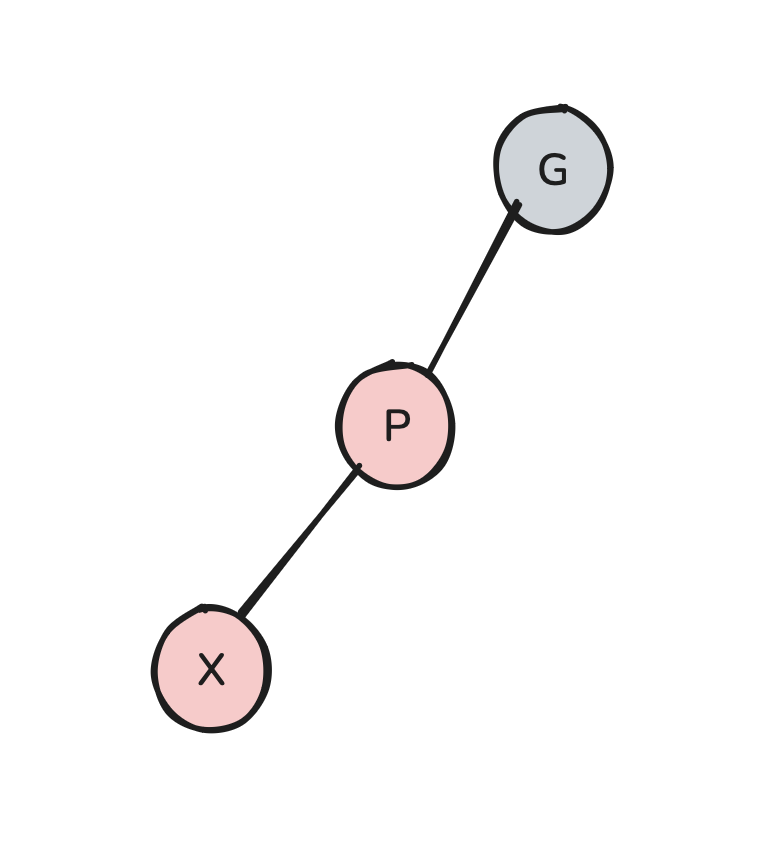

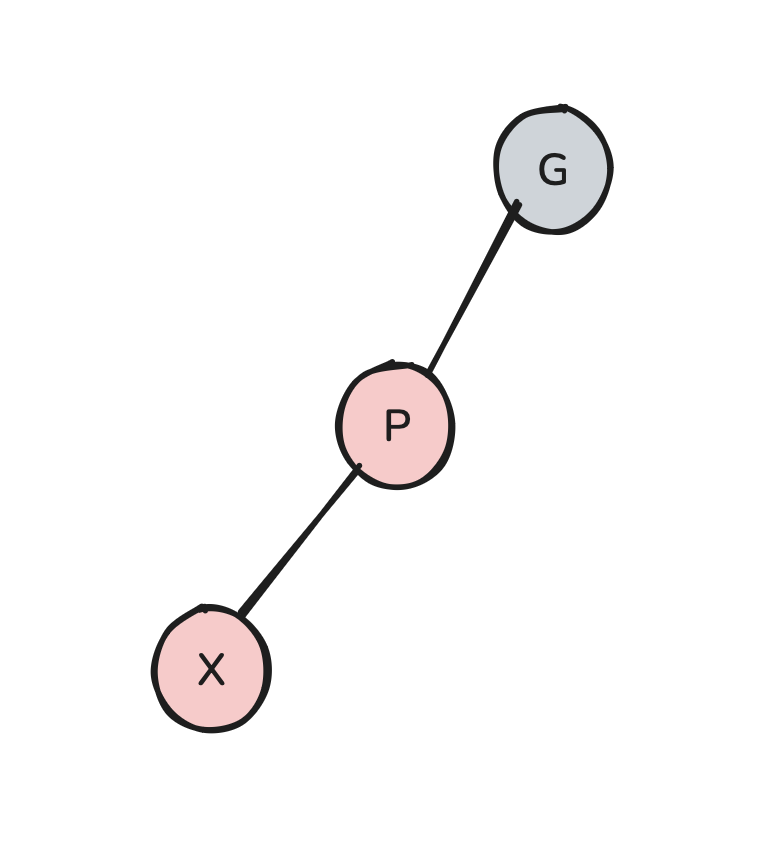

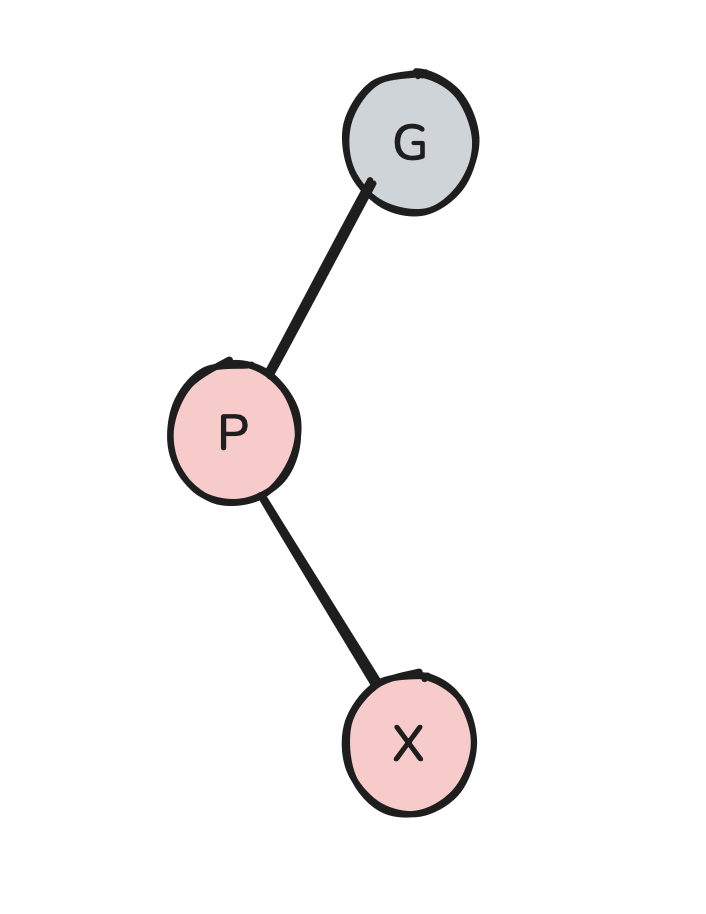

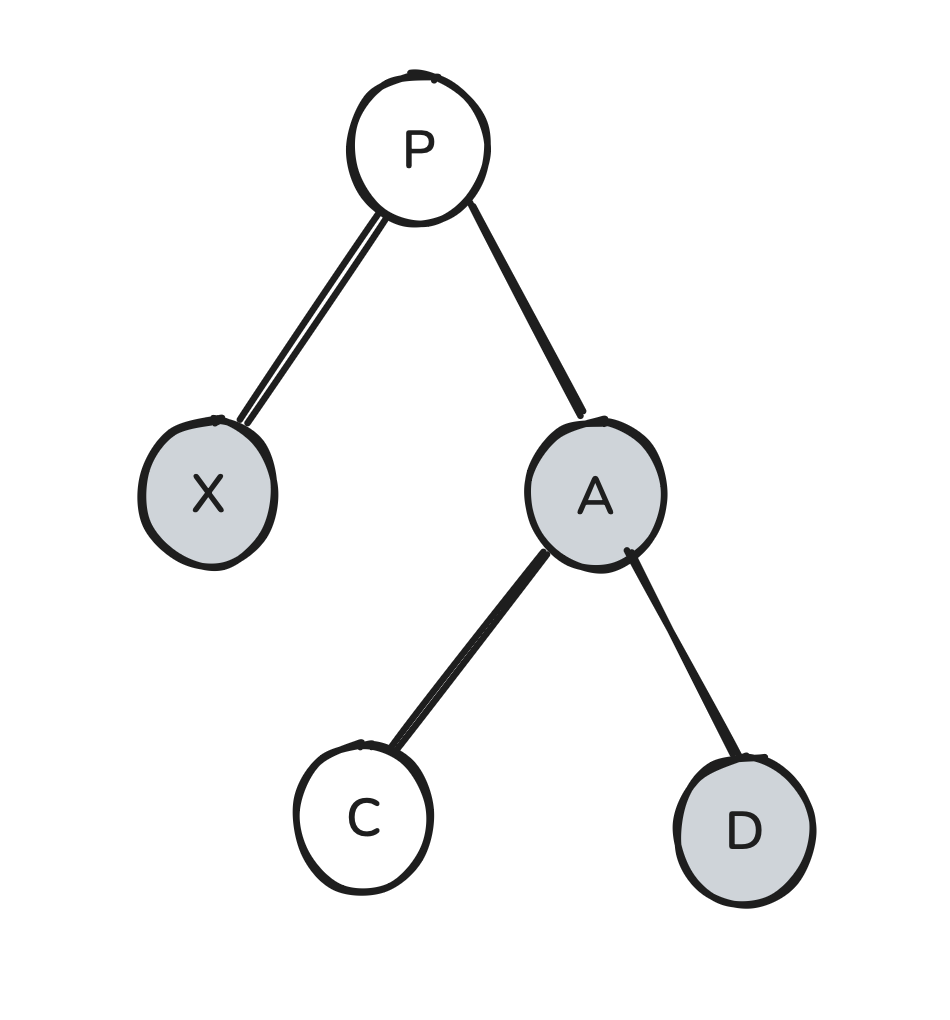

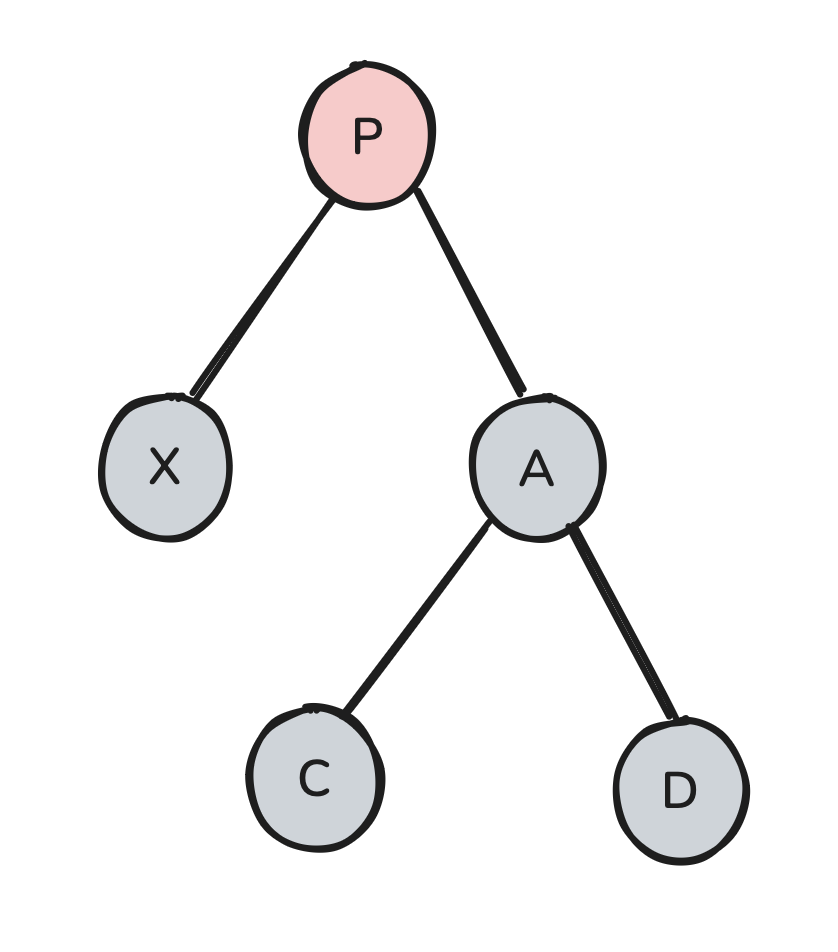

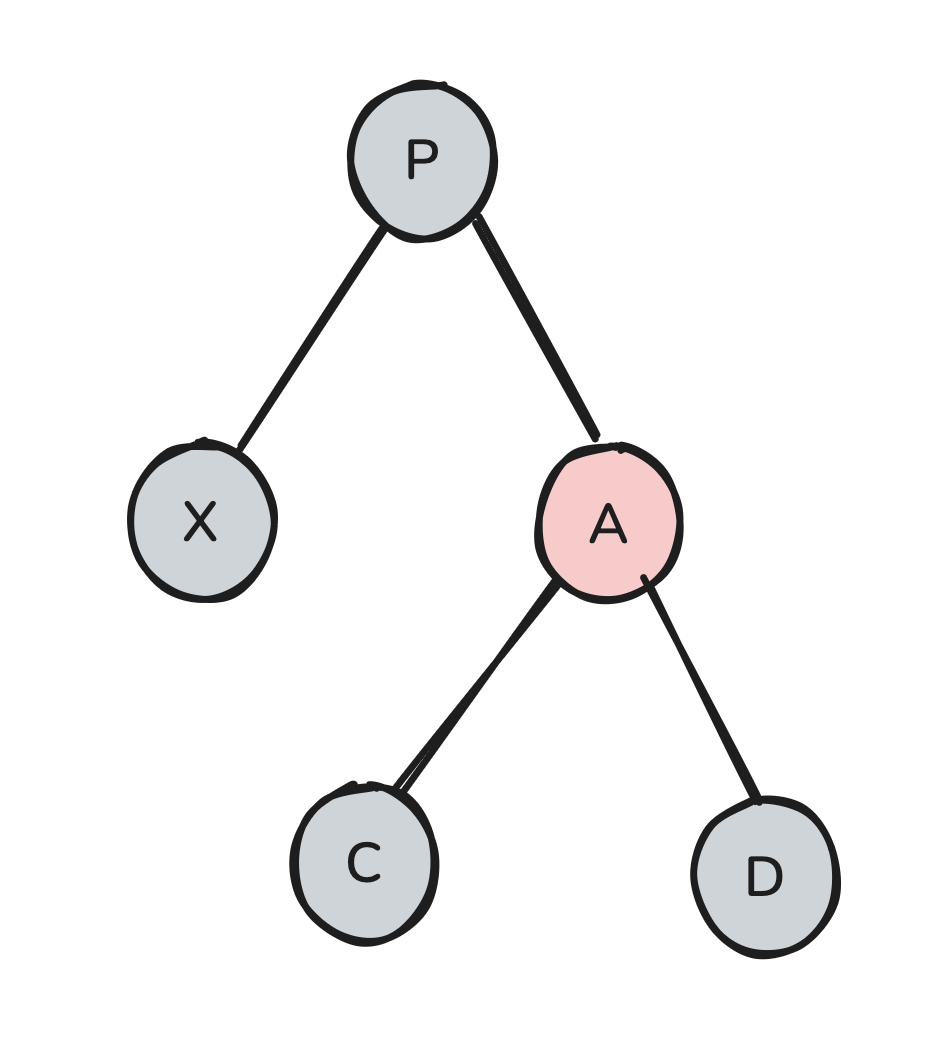

Let the new node we’ve added be X. If X’s parent is black, then no rule has been violated and we are done. So suppose X’s parent is red. We must fix a red rule violation. Since X’s parent is red, we can deduce that X’s grandparent is black. So we have some situation like this:

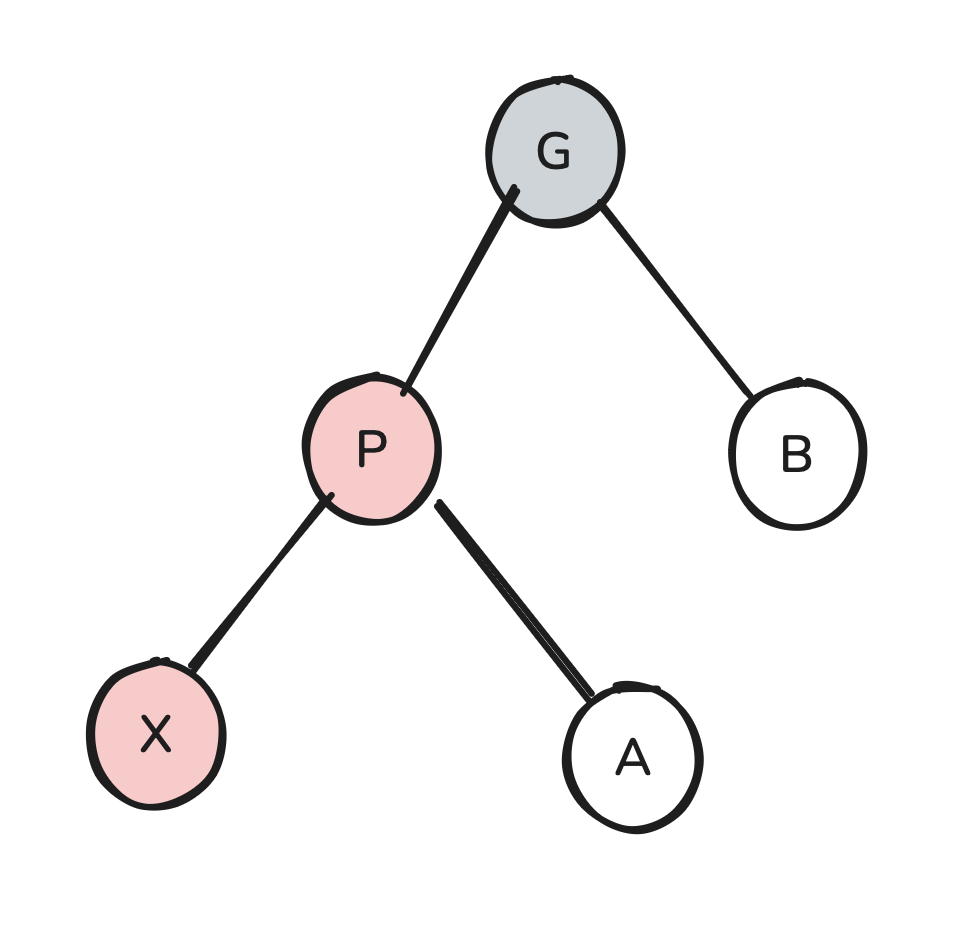

We’ve labeled X’s parent P and X’s grandparent G. Let’s also add in the additional (possibly null) children. We’ll leave these nodes white to indicate that they can be any color.

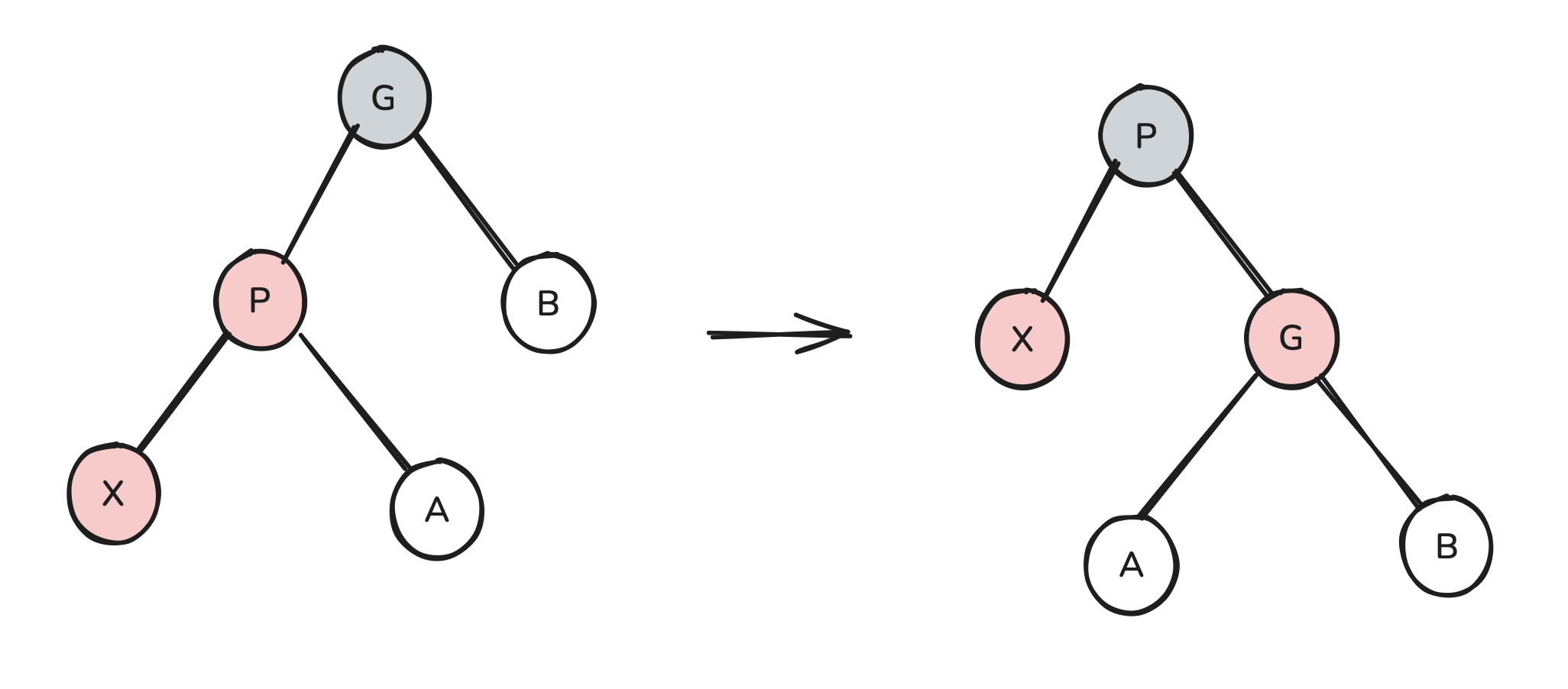

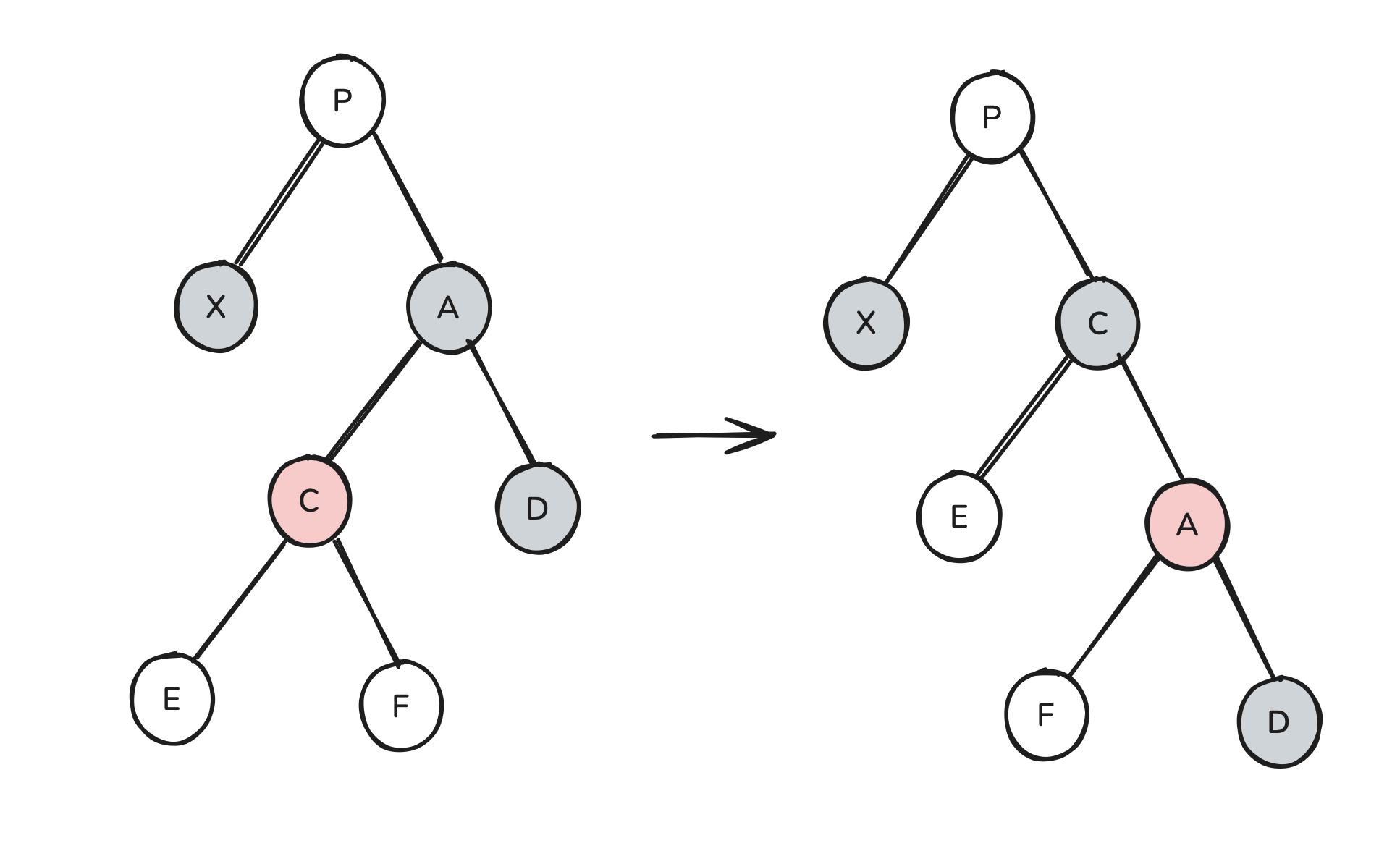

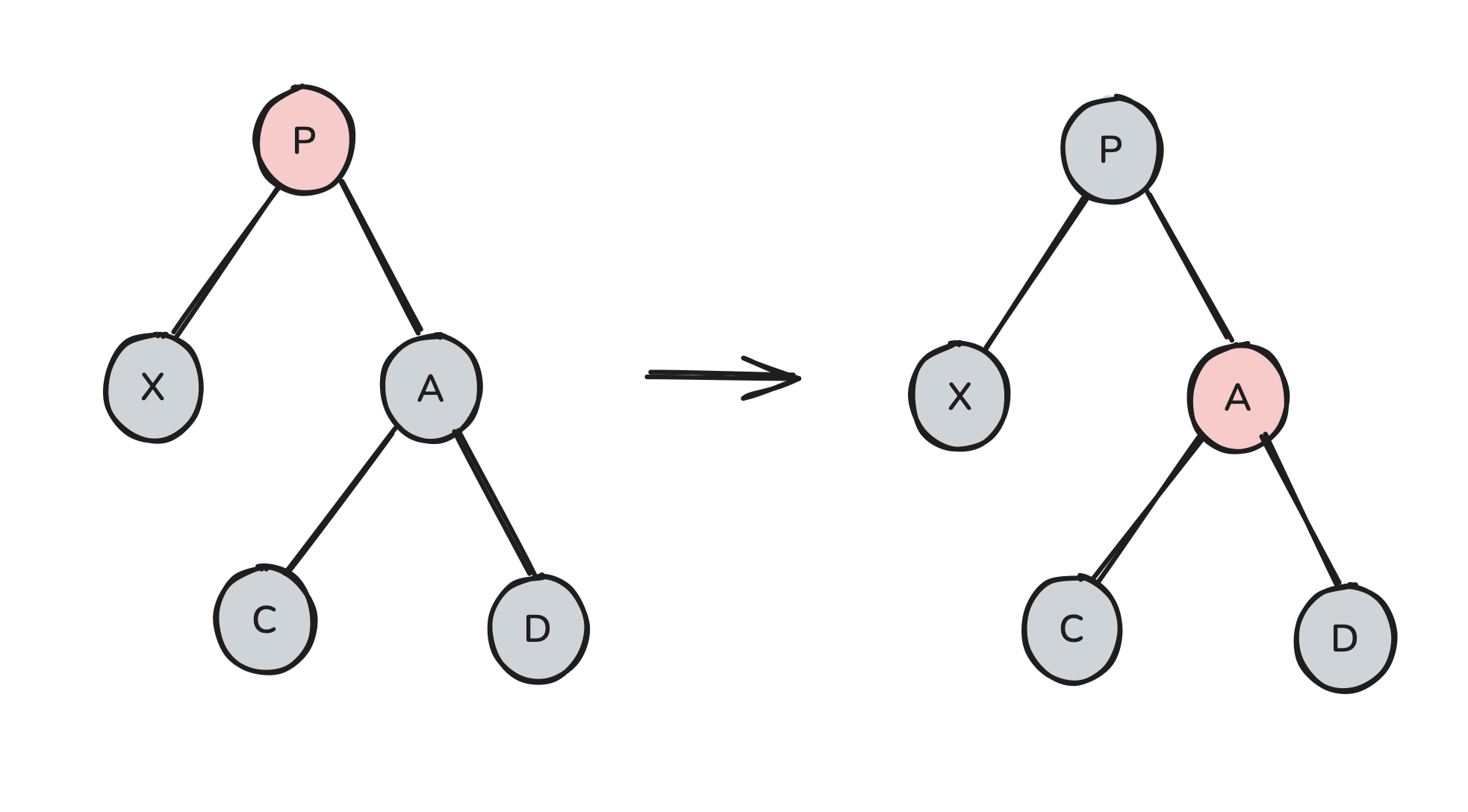

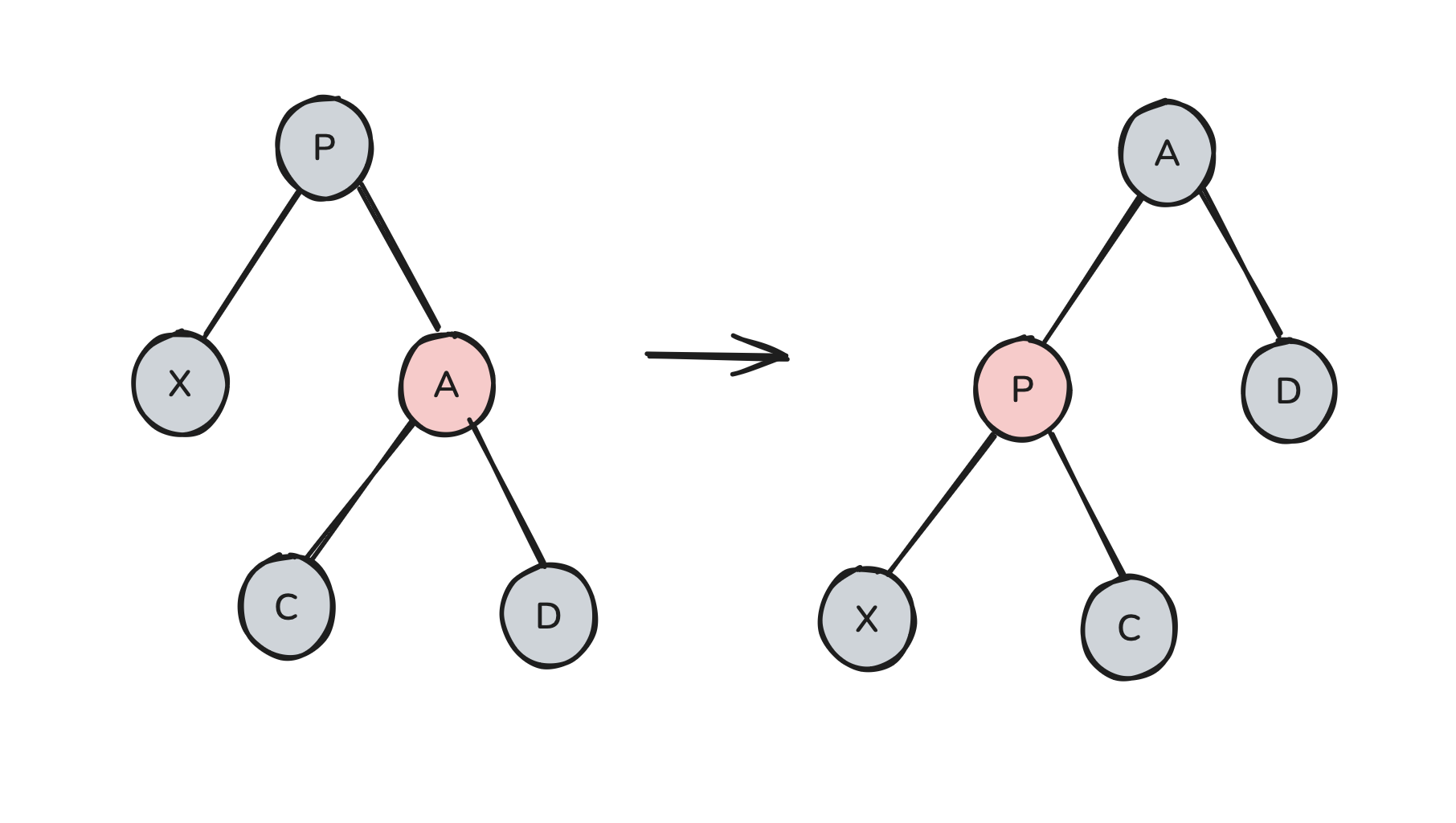

We need some way to separate X from P so that the two red nodes are no longer adjacent. Recalling what we’ve just discussed about the rotate-swap operation, we observe that because P is red, we can rotate-swap it into G without risk of violating the black rule. Moreover, doing so seems to fix our problem of having two adjacent red nodes:

Great! We’ve just rebalanced our tree with a single rotate-swap. There is one problem, though. If B is red, then it is now in contact with a red node, which is not allowed. (We don’t have this issue with A because A couldn’t have been red in the original tree).

So we conclude that we can only use this technique to fix our tree if B is black.

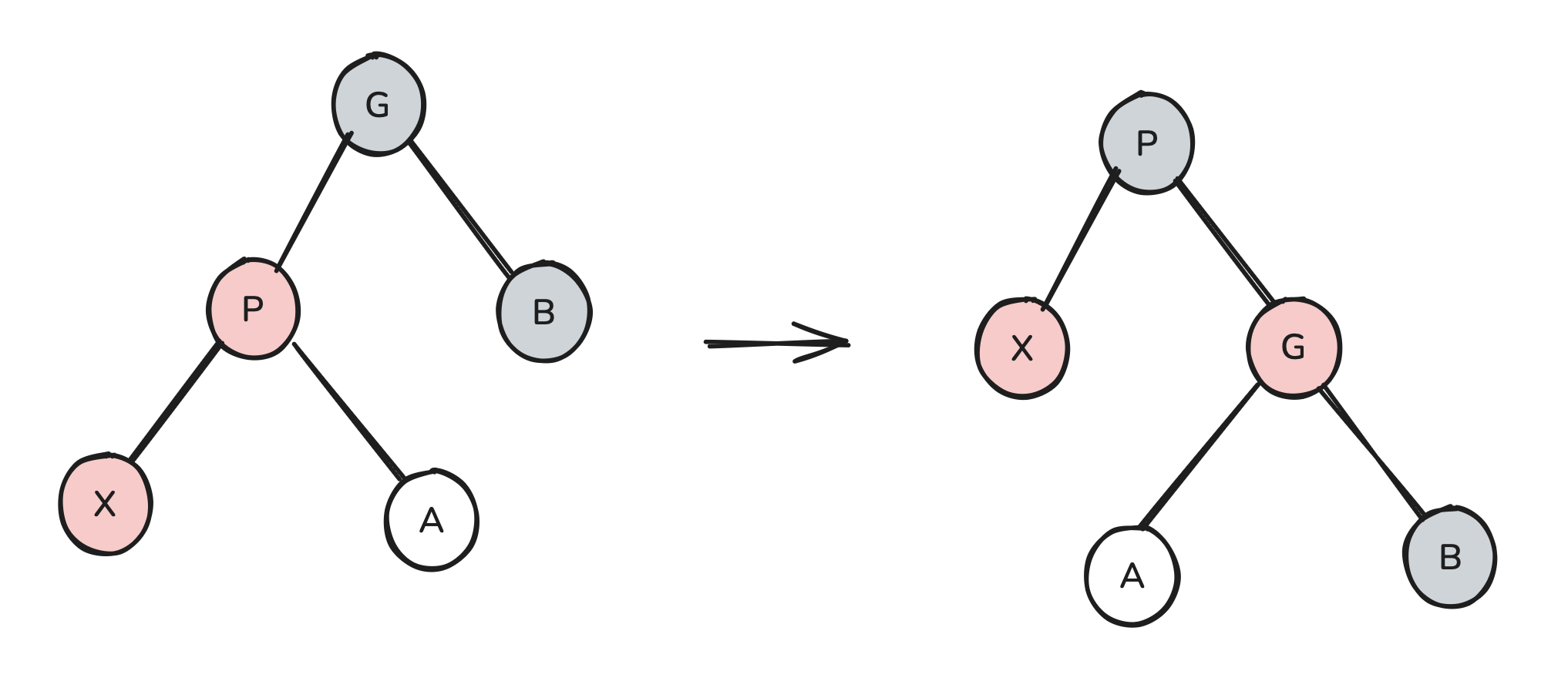

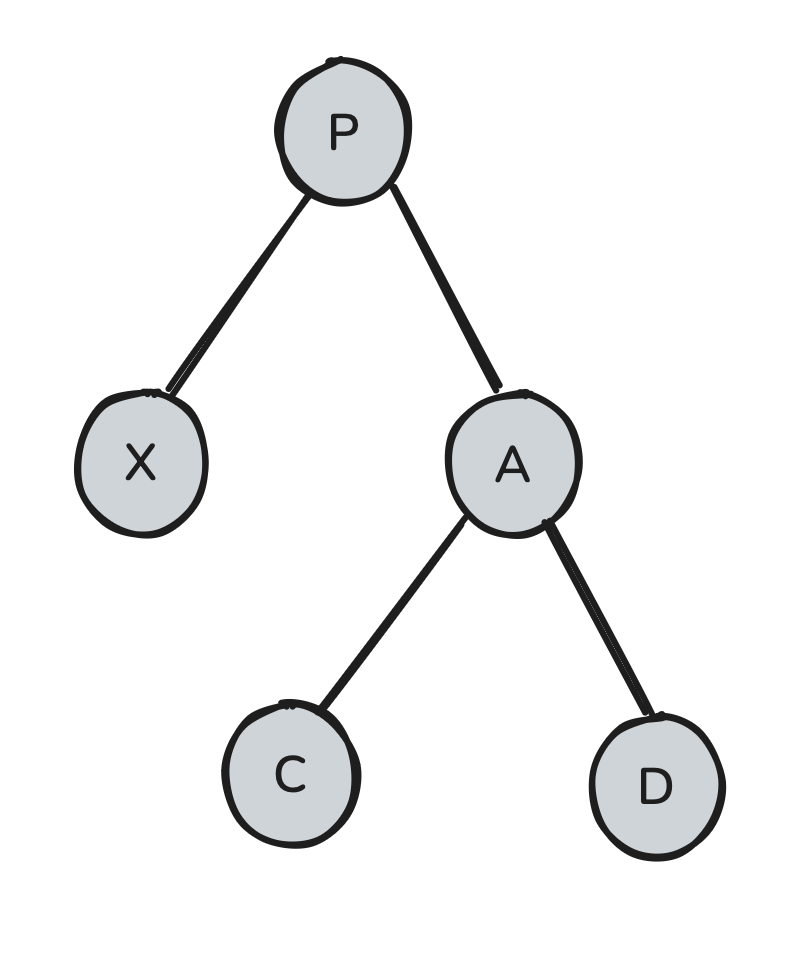

Okay, so let’s think about what we can do if B is red.

Here, we can do something simpler. We actually don’t need any rotations at all. We can simply color P and B black, and then color G red.

This recoloring preserves the black rule and also gets rid of the two adjacent red nodes. It is however possible that we’re still violating the red rule, because G’s parent in the recolored tree could be red. However, this is fine because what we’ve essentially done is shifted our problem two levels up the tree. Meaning we can now run our same algorithm on the subtree two levels up. Eventually, if we recurse up to the root, we will have a situation where the root is red and one of its children is red, and in that situation we just color the root black and we are done.

Great! We’ve now fully solved the case when we have an arrangement like this:

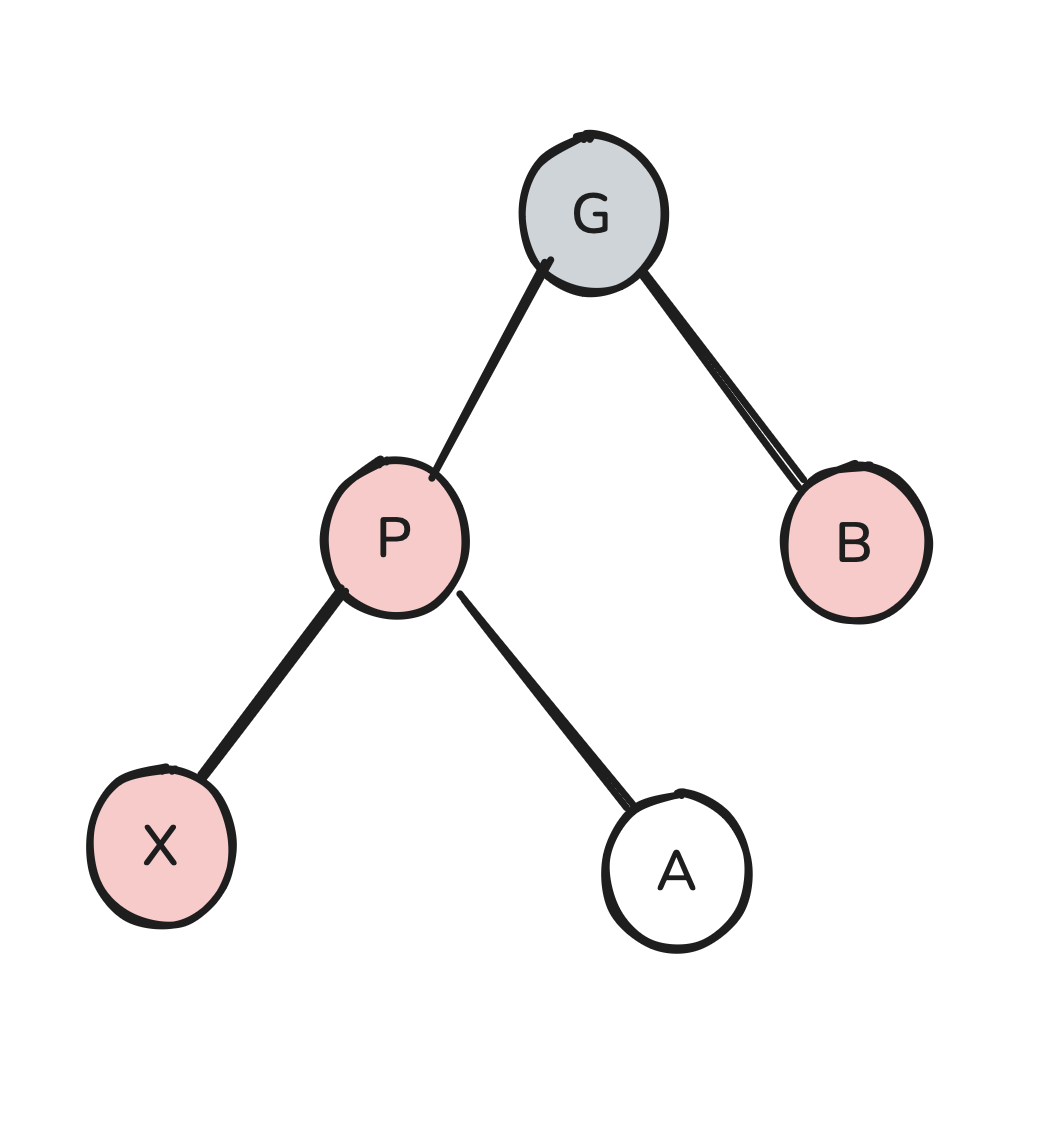

However, we haven’t yet considered the following possibility:

X could be an “inner grandchild.” In this case, rotating-swapping X’s parent into its grandparent won’t actually work because X will end up in contact with a red node. Our goal is to try to transform this arrangement into one in which our red child is an outer grandchild. It doesn’t take long to realize that we can do this by simply rotate-swapping X into its parent. Once again, we can do this freely because X is red, and a red rotate-swap will not result in a black rule violation.

We’re now in a situation where our red child is an outer grandchild, which we know how to deal with. Thus we’ve now solved all possible cases for insertion.

Let’s now think about deletion. Nodes with at least one child can be deleted pretty easily:

If the node has no children and is red, we can simply delete it.

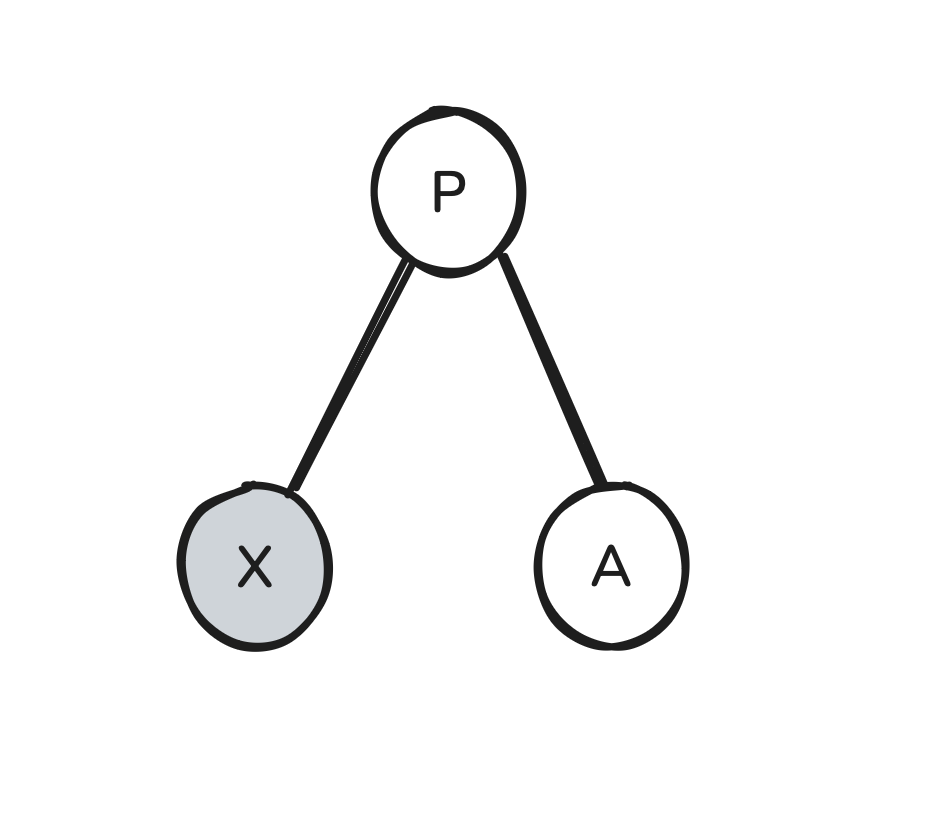

If the node has no children and is black, we will need to do some work. We begin by setting the node to null.

Here, X is our null node. Note that X’s sibling A cannot be null because if it was, the original tree would have violated the black rule.

We are in a situation where the path from the root to X has one fewer black node than it should. Thus we must somehow add a black node to the path from the root to this node. This is difficult because if we simply try to recolor a red node along this path black, we will fix the path to X but will add an extra black node to all other paths containing that recolored node.

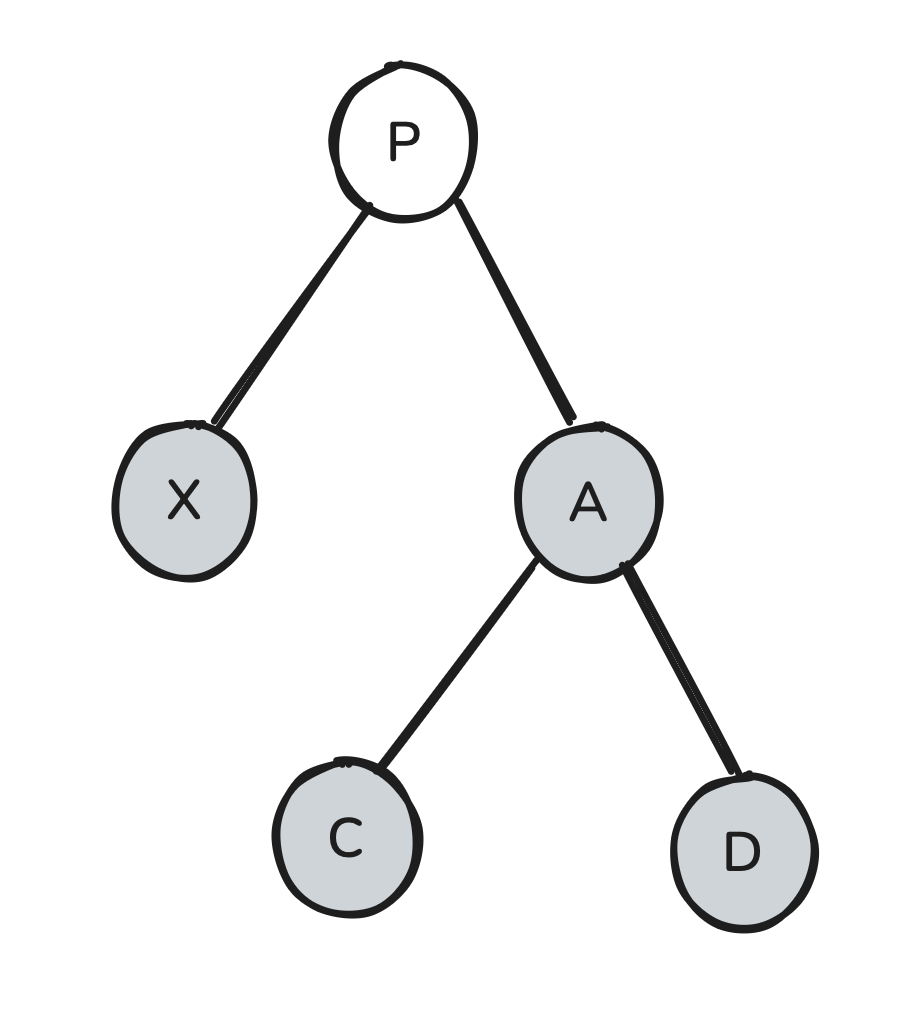

Recall that a black rotate-swap can be used to transfer a black node from one subtree’s ancestry to another’s. We could try to use a black rotate-swap to add a black node to X’s ancestry. However, we would then be left with a subtree which lacks a black node. If that subtree’s root happened to be red, then we could recolor its root black and we would have fixed our tree. So we seem to have solved for one possible case:

Here, A is the black node being “transferred” from D’s ancestry to X’s ancestry. We subsequently change D’s color from red to black to restore its black node count. Note that this technique can be used to fix our tree regardless of what P’s original color was.

So we seem to have solved a case where both of the following are true:

So we must now consider the cases when one or both of the above conditions aren’t true.

Let’s first consider what we can do if D is black:

If we got X’s sibling to have a red right child instead of a black one, we’d be able to apply the same set of operations we’ve used above to fix the tree.

If C is red, it doesn’t take long to see that we can achieve this through a red rotate-swap:

We can now proceed with our original strategy: rotate-swap C into P and then recolor A to be black.

So what if C is black?

How we proceed will depend on the color of P. Suppose that P is red:

Here, we can fix our tree by doing something incredibly simple: swap the colors of P and A:

Our tree is now fixed.

What if P is black?

Here, there seems to be nothing we can do. If every node is black, how can we possibly add an additional black node to X’s ancestry?

We can’t. However, what we can do is shift our problem up the tree. If we recolor A red, then we will have transformed our tree from one in which X’s subtree is missing a black node to one in which both X’s and A’s subtrees are missing a black node. Thus the entire subtree rooted at P is missing a black node. We can therefore restart our algorithm but with P as our new X. If we eventually recurse up to the root of the tree, then we will have decreased the black node count of all paths by one and our tree will be fixed.

We’ve now fully solved the case where X’s outer nephew (D) is black.

At this point, we know how to fix the tree in any of the following cases:

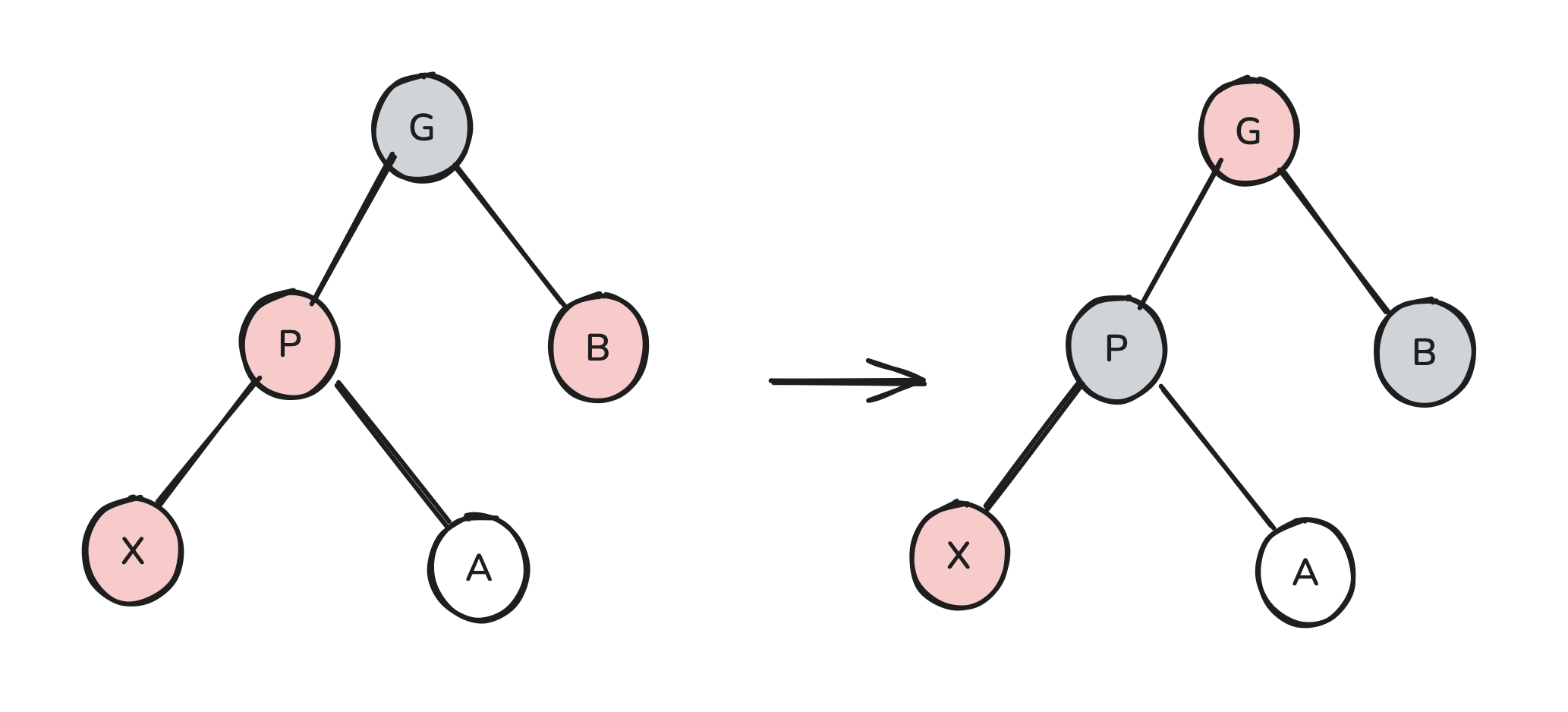

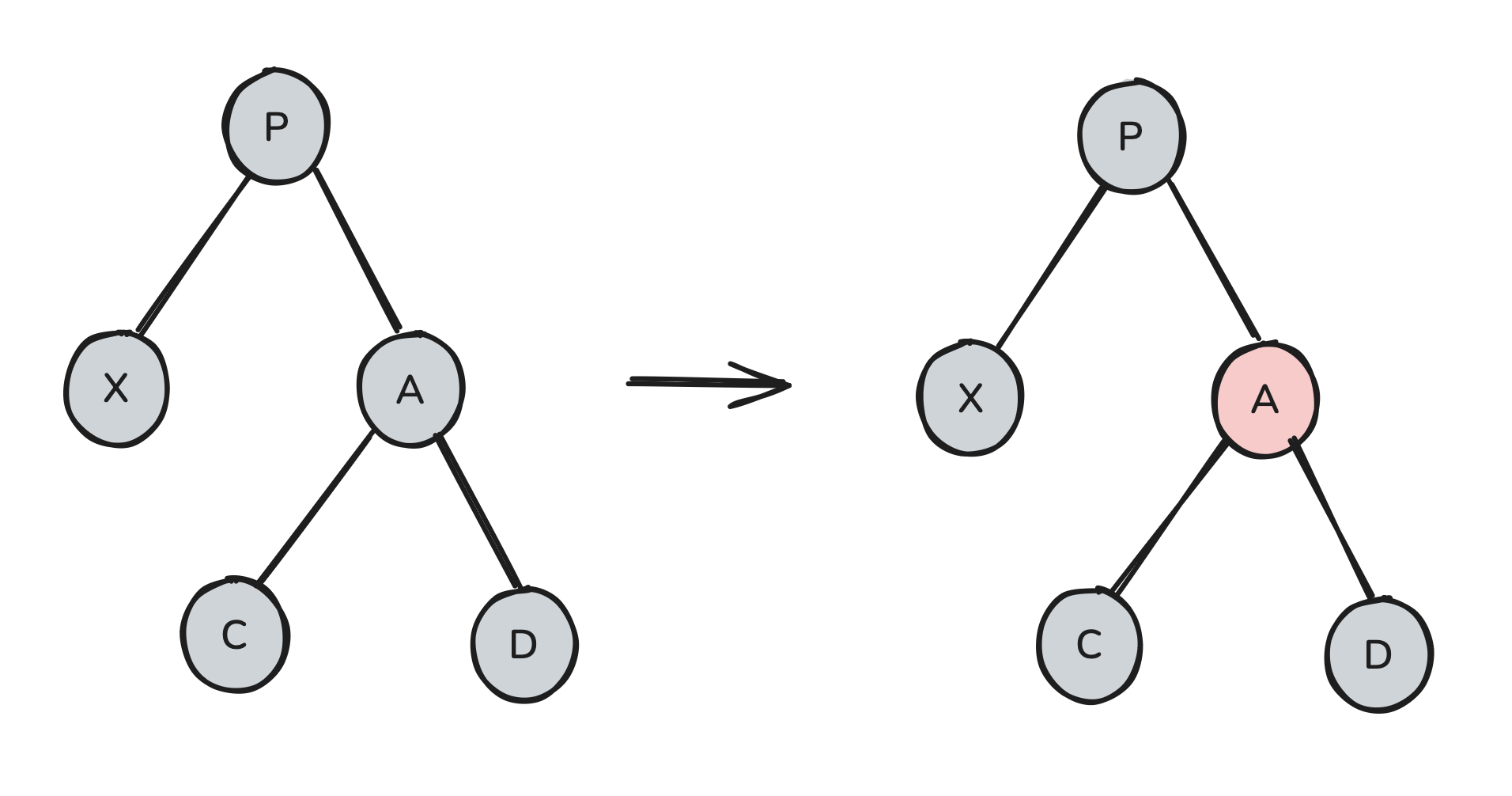

So all that’s left is to figure out what we will do if X’s sibling (A) is red. Note that X’s sibling being red fully determines the colors of all other nodes in the diagram:

In this scenario, there doesn’t seem to be much we can do. However, because we know that we can perform a red rotate-swap for “free”, let’s just try doing that. It may transform our tree into something that we know how to handle:

Now, X’s sibling is no longer red. Thus we have transformed the tree into a case that we know how to solve, and we are done.

We’ve now solved all possible cases for deletion.